Periodontal disease as a possible risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases in a Greek adult population

Introduction

A large amount of people in Greece have been affected by several types of periodontal disease, such as gingivitis and periodontitis. Recent studies have not been performed regarding the prevalence/incidence of PD in Greece, however, a recent one recorded that 27.5% of Greek adults aged 35–44 years old had shallow and deep pockets, whereas 9.5% of the subjects examined showed healthy periodontium. It was also showed that the prevalence of severe PD in Greek adults was not high and their periodontal health had improved since 1985, whereas a corresponding decrease in gingivitis prevalence was not observed (1).

PD and especially periodontitis is a chronic progressive inflammatory disease and characterized by inflammation of the periodontal tissue and destruction of periodontal fibers and alveolar bone.

It has also been suggested that several bacteria and their antigens, endotoxins and inflammatory cytokines and chemokines show elevated levels due to chronic periodontitis and activate a systemic inflammatory reaction (2,3).

Several researchers and clinicians have observed that periodontal infection contributes to periodontitis and leads to systemic effects as significant associations have been recorded between PD and systemic diseases or disorders such as atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (ACVD), respiratory diseases and allergies, hypertension (HT), diabetes mellitus, endocrine disorders, cancer etc. (4).

ACVD is a group of vessels and heart disorders and include coronary heart disease and artery diseases (CHD/CAD) such as myocardial infarction and angina, cardiac arrhythmias (CA), stroke, hypertensive heart disease, cardiomyopathy, rheumatic heart disease, aortic aneurysms, endocarditis, cerebrovascular disease, etc. (5). ACVD consists also the main cause of death in economically developed countries (6), whereas genetic influences in combination with environmental and behavioural risk factors have been suggested as its pathogenic factors (7).

It is well-known that many risk factors, such as age, male gender, HT, marked obesity, abnormal lipid metabolism, diabetes mellitus (8,9), cigarette smoking and physical inactivity socio-economic status, diet (8) are involving in causing ACVD, however its etiology remains still unknown as many clinical and epidemiological aspects need to be clarified (10). The role of systemic chronic inflammation in ACVD pathogenesis has also been proposed (11).

Previous reports have recorded associations between male gender, smoking, diabetes mellitus, low socio-economic level and dyslipidemias as ACVD causative risk factors and PD development (12,13).

According to the mentioned observations a role of PD in ACVD etiology (11) has been suggested, whereas a significant association has been observed between PD and elevated serum levels of chronic inflammation biomarkers such as cytokines and chemokines (14).

Recent cohort and case-control researches have reported an association between PD and ACVD (4,15-21) whereas, few ones have shown no associations between both diseases (22-27). A small number of previous studies have investigated the possible association between chronic periodontitis and HT, leading in inconsistent findings and focusing the need for more research (28-30).

A possible relationship between PD and ACVD could be attributed to the fact that both diseases characterized by common causative/risk factors, such as smoking, low socio-economic status and diabetes mellitus (31). Their pathogenesis also characterized by elevated serum levels of inflammatory biomarkers such as C reactive protein (CRP) and fibrinogen (32). Periodontal bacteria or their products affect directly the vascular endothelial cells because of bacteremia or indirectly because of the inflammatory reaction, conditions that can lead to ACVD pathogenesis (33).

It has also been suggested that genetic factors influence the biological progression of both diseases and based on that observation, the possible association between both diseases was suggested (34), although those factors remain to be discovered.

The purpose of the current research was to examine the possible relationship between periodontal diseases clinical variables and ACVD in a sample of Greek individuals.

Methods

Study sample

The current retrospective cross-sectional population-based study involved the cities of Patra, Rio, Kato Achaia and four surrounding villages. The participants were permanent inhabitants of the mentioned locations and based on each community population size were drawn at random. In order to be acquired a representative study sample the study population was stratified by age and gender. Thus, a sample of 1,850 individuals, 938 males and 912 females aged 49 to 80 years was invited to participate.

All the participants were patients of a private dental and two private medical practices, were interviewed by filled in a medical and a dental health questionnaire and undergone an oral clinical examination. The research was performed between December 2014 and November 2015.

Patient selection criteria

Participants’ selection criteria comprised age from 49 to 80 years old. The minimum number of the participants’ natural teeth should be at least 20, since less than 20 teeth could lead to over- or underestimation of the parameters and the possible relationships examined.

All participants ought not to have been received conservative or surgical periodontal treatment during the previous six months or systemic antibiotics or anti-inflammatory or other systemic medication during the previous six weeks. Out-patients suffered from acute infections, malignant diseases, or received medication with systemic glucocorticoids treatment, were not included in the research. The mentioned criteria were determined in order to limit possible influences due to known or unknown confounders on the study variables examined and because of potential effects of those conditions on the oral and periodontal tissues. Third molars and remaining roots were also not included in the research.

Oral clinical examination

A well-trained and calibrated dentist was performed participants’ oral clinical examinations and the following clinical parameters were recorded: gingival index (GI), probing pocket depth (PPD), clinical attachment loss (CAL) and bleeding on probing (BOP) were measured by a William’s 12 PCP probe (PCP 10-SE, Hu-Friedy Mfg. Co. Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) at six sites (lingual, facial, disto-lingual, mesio-lingual, disto-facial and mesio-facial).

The severity of PPD and CAL was coded according to the criteria of ‘clinically established periodontitis’ (35).

The severity of gingivitis was coded according to the following clinical signs: no pathological condition of gingiva/mild gingival inflammation which refers to Löe and Silness (36) classification as score 0 and 1; moderate/severe gingival inflammation, which refers to Löe and Silness (36) classification as score 2 and 3.

The presence of PPD was coded according to the following clinical signs (37): score 0—periodontal pockets with moderate depth, 4–6.0 mm; score 1—advanced periodontal pockets with advanced depth, >6.0 mm.

The severity of CAL coded according to the following clinical signs (38): score 0—mild attachment loss, 1–2.0 mm; and score 1—moderate/severe attachment loss, ≥3.0 mm. PPD and CAL records were estimated according to the immediate full millimetre. The presence or absence of BOP was coded according to the following clinical signs: score 0—BOP absence; and score 1—BOP presence and determined as positive in case the reaction was occurred within 15 seconds of probing.

Questionnaire

All individuals that participate in the study completed a medical and dental questionnaire which contained clinical parameters such as sex, age, smoking habits (current, previous/no-smokers), educational and socio-economic level and information that concerned their medical history, medication, several chronic or systematic diseases or pathological conditions and the frequency of participants’ dental follow-up. For the mentioned aim a modified University of Minnesota Dental School Medical Questionnaire (39) questionnaire was used and was included ACVD’s four subgroups that are CHD, heart attack (HA), HT and CA.

The main question for the participants was if they ever had a disease or disorder that had been diagnosed by a MD. Participants’ medical files were used in cases they were not able to mention details of their medical history concerned the clinical parameters examined.

In order to assess the intra-examiner variance, a randomly chosen sample consisted of 370 (20%) participants was undergone another clinical dental examination by the same dentist after 3 weeks. After consideration of the protocol numbers of the double examined individuals no differences were estimated between both clinical assessment (Cohen’s Kappa =0.97) whereas no oral hygiene instructions were given to the study population for 3 weeks.

Ethical consideration

The present retrospective cross-sectional population-based study was an epidemiological study that was not based on experimental process, as in Greece authorized committees must approve issues regarding the ethical consideration e for experimental researches only.

Individuals who accepted the invitation to take part in the present research informed about the aims of it a consent form was signed by them. The present research has been carried out in full agreement with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

The worst values of the indices examined at the six sites per tooth were assessed and coded as dichotomous variables for each participant.

Males individuals, current and previous smokers, subjects with a high educational (graduated from University/College) and socio-economic (income equivalent to or above 1,000 €/monthly) level and participants that had the proper frequency of a dental follow-up were coded as 1. A multivariate regression analysis was applied out to test the associations between the dependent variable, ACVD and the mentioned medical conditions separately, and independent ones that were determined by the initial (enter) method. The model was also used to assess adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Finally, after performing of the stepwise method was assessed gradually which independent variables showed significant associations with ACVD that is the dependent one.

The statistical package of SPSS ver. 17.0 was used for performing of statistical analysis whereas a p value less than 5% (P<0.05) was determined to be statistically significant.

Results

The participants had a mean age of 58.4±2.8 years.

A total of 1,968 individuals were invited to participate in the present investigation. The 47 participants were not permanent inhabitants of Patra Rio, Kato Achaia and the surrounding villages and were not included in the study sample, 32 participants did not meet the mentioned inclusion criteria as they had less than 8 remaining teeth or they had received systemic antibiotics or anti-inflammatory drugs for a large period, whereas 39 participants kindly refused to take part in the study. Finally, the study sample consisted of 1,850 out-patients giving a response rate 94.0%. Current smokers reported 58.9% of the study sample, 32.5% males and 26.4% females.

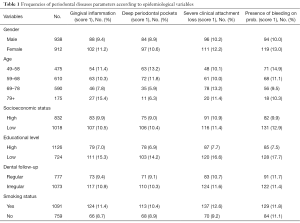

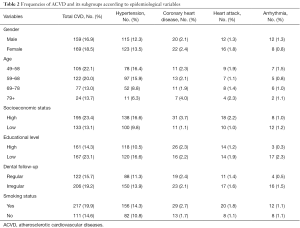

Table 1 presents oral variables frequencies of the total study-population that was answered the questionnaire and in the mentioned ACVD’s subgroups. ACVD’s frequencies of the parameters examined in all participants and in the subgroups are presented in Table 2.

Full table

Full table

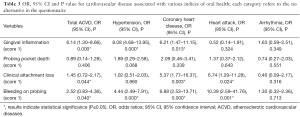

Logistic regression analysis model showed an association between gingival inflammation and all ACVD, HT, and CHD. Associations were found between CAL and all ACVD, BOP and all ACVD, CAL and HA, CAL and CHD, BOP and HA, BOP and CHD, and BOP and HT (Table 3).

Full table

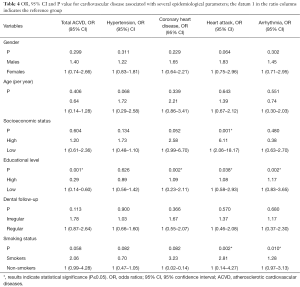

Associations were also recorded between smoking and all ACVD, higher educational level and all ACVD except for HT, and higher socio-economic status and HA and CHD. No associations were observed between all ACVD and gender, age and dental follow-up (Table 4).

Full table

Discussion

The present study showed that gingival inflammation could be an index of an increased risk of ACVD. Individuals with gingival inflammation had an OR of 6.14 to suffer from any kind of ACVD, such as CHD and HT. HT showed a particularly significant association with inflammatory gingiva. This observation is important, since it is one of the main risk factors for ACVD (40). A link between gingival inflammation and HT was also observed in a study by Buhlin et al. (41). Gingival inflammation was associated with CHD, observation that is in agreement with previous studies (42,43), whereas no association was observed between those variables in a report by Chrysanthakopoulos et al. in Greek adults (44).

No association was recorded between PPD and ACVD, finding that was confirmed by previous reports (41,42). Similarly, no associations were recorded between the subgroups of ACVD examined and periodontal pockets.

This observation suggests an association between gingival inflammation and ACVD, but not between periodontitis and ACVD. Morrison et al. (45) showed that the relative risk of dying of CHD was higher in individuals suffered from mild or severe gingivitis than in those with periodontitis. Hung et al. (43) were recorded that PPD could be an indicator for traditional risk factors for CHD and Pejcic et al. (46) were observed a strong association between serum bio-markers of PPD and ACVD biomarkers such as lipoproteins.

Similarly, Starkhammar-Johansson et al. (47) found that CHD patients had significantly higher rates of deep periodontal pockets 4–6.00 mm. In another study, classified periodontitis (48), was found to be significantly associated with CHD presence (49). A case-control study by Latronico et al. (50) supported that deep periodontal pockets seemed to be important risk factors for ACVD.

However, other reports did not confirm such findings (24,51,52). A link between HT and PPD was recorded in a previous report (53), finding that was not in agreement with the current report and similar ones (41,51,52) whereas a small number of previous studies have investigated the possible association between chronic periodontitis and HT leading to inconsistent results and highlighting the need for further research (28-30).

The current study revealed an association between HA and PPD, finding that was in accordance with the one of a recent report (53). CAL was found to be associated with ACVD, however this association was most notably in individuals suffered from CHD and HA. Similar findings were recorded in previous studies (43,46,51). In addition, Tuominen et al. (54) recorded a significant association between CAL and HT and CAL and HA, however other reports did not confirm such observations (42,44,52).

The current study also recorded that, a total of 11.5% showed BOP, in both males and females and a strong association between BOP and ACVD was recorded. The mentioned association was most marked in patients with CHD, HT and HA but not in those with CA.

Similar results regarding all ACVD and BOP, and HT and BOP were observed in a previous report (41), whereas Pejcic et al. (46) found an association between CHD and BOP, and Chrysanthakopoulos et al. (52) observed an association between ACVD and BOP, whereas in the same study no associations were observed between BOP and HT.

Those contradictory results, with OR’s ranging between over 1.0 and almost 1.0 indicate that the possible association examined is complicated and several factors have been involved. Those factors must be methodically clarified before an association between ACVD and periodontitis can be conclusively recorded.

Tobacco smoking was associated with ACVD and particularly strong associations were observed in individuals suffered from CHD and HA. This finding shows that ACVD is a strong incitement for cessation of smoking.

Similarly, higher educational level was associated with all subgroups of ACVD except for HT, whereas higher socio-economic status was associated with CHD and HA. Previous reports have recorded either no association after adjustment for parameters considered to be confounders or non-significant positive trends (54,55) whereas Bokhari and Khan (23) suggested that the available researches regarding the link between of PD and ACVD are inconclusive and most of their data is based on epidemiological and not on experimental investigations.

The current study has certain limitations that should be considered during the procedure of interpreting the results section. In a retrospective study, like the present, the reliability is not as high as for prospective ones since the inter-examiner variability is most likely higher. In addition, random and recall biases and the effect of known and unknown confounders are likely higher. Another limitation was that the study information based on the individuals’ responses to the questionnaire. Therefore, the participants could not response to some of the questions or could over- or under-estimate their potential medical problems and this situation could lead to restrictions on the study validity during the results interpretation. Despite the fact that participants’ data collection could be collected by their own medical files this procedure could lead to epidemiological biases regarding results validity. Finally, it was not clear whether gingivitis or periodontitis precede ACVD and because of that, it is difficult to establish a causal relationship between diseases examined.

Based on the fact that gingivitis or periodontitis precede ACVD it is of vital importance to take into account that the period from exposure to disease appearance is at best short in relation to the CV system alterations. In addition, a possible underestimation of older individuals who suffered from PD and who may have lost their teeth due to periodontal reasons could be occurred because of the decision to be included in the study sample protocol older participants who had at least 20 remaining natural teeth. Another limitation was that in the present study were recorded conventional periodontal parameters, whereas in similar studies different and more reliable PD parameters such as alveolar bone height or loss or the total number of remaining or missing teeth have been used.

Conclusions

The current investigation recorded an association between ACVD and gingival inflammation, CAL and BOP, without indicating the nature of such an association, or the possible causal role of PD in ACVD development. For that reason further research is needed.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study needs no approval of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) as it was not an experimental one and based on questionnaires and simple dental examinations. All enrolled patients had not been examined by clinical examination as the diagnosis of several ACVD forms had been set before the study design.

References

- Mamai-Homata E, Polychronopoulou A, Topitsoglou V, et al. Periodontal diseases in Greek adults between 1985 and 2005-Risk indicators. Int Dent J 2010;60:293-9. [PubMed]

- Socransky SS, Haffajee A. Microbial mechanisms in the pathogenesis of destructive periodontal diseases: a critical assessment. J Periodont Res 1991;26:195-212. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Page RC. The pathobiology of periodontal diseases may affect systemic diseases: inversion of a paradigm. Ann Periodontol 1998;3:108-120. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jepsen S, Kebschull M, Deschner J. Relationship between periodontitis and systemic diseases. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2011;54:1089-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanz M, D’ Aiuto F, Deanfield J, et al. European workshop in periodontal health and cardiovascular disease scientific evidence on the association between periodontal and cardiovascular diseases: a review of the literature. Eur Heart J 2010;12 Suppl:B3-12. [Crossref]

- World Health Organization. The world health report: Bridging the gaps. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1 (1995).

- Hegele RA. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Clin Chim Acta 1996;246:21-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keil U. Coronary artery disease: the role of lipids, hypertension and smoking. Basic Res Cardiol 2000;95:I52-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scannapieco FA, Bush RB, Paju S. Associations between periodontal disease and risk for atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, and stroke. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol 2003;8:38-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Helfand M, Buckley DI, Freeman M, et al. Emerging risk factors for coronary heart disease: a summary of systematic reviews conducted for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:496-507. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, et al. C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med 2000;342:836-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Genco RJ. Current view of risk factors for periodontal diseases. J Periodontol 1996;67:1041-9. [PubMed]

- Katz J, Flugelman MY, Goldberg A, et al. Association between periodontal pockets and elevated cholesterol and low density-lipoprotein cholesterol levels. J Periodontol 2002;73:494-500. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu T, Trevisan M, Genco RJ, et al. Examination of the relation between periodontal health status and cardiovascular risk factors:serum total and high density lipoprotein cholesterol, C-reactive protein, and plasma fibrinogen. Am J Epidemiol 2000;151:273-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blaizot A, Vergnes JN, Nuwwareh S, et al. Periodontal diseases and cardio-vascular events: meta-analysis of observational studies. Int Dent J 2009;59:197-209. [PubMed]

- Davé S, Van Dyke T. The link between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease is probably inflammation. Oral Dis 2008;14:95-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oe Y, Soejima H, Nakayama H, et al. Significant association between score of periodontal disease and coronary artery disease. Heart Vessels 2009;24:103-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pinho MM, Faria-Almeida R, Azevedo E, et al. Periodontitis and atherosclerosis: an observational study. J Periodontal Res 2013;48:452-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sfyroeras GS, Roussas N, Saleptsis VG, et al. Association between periodontal disease and stroke. J Vasc Surg 2012;55:1178-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shrihari TG. Potential correlation between periodontitis and coronary heart disease-an overview. Gen Dent 2012;60:20-4. [PubMed]

- Xu F, Lu B. Prospective association of periodontal disease with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: NHANES III follow-up study. Atherosclerosis 2011;218:536-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beck JD, Eke P, Heiss G, et al. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease: a reappraisal of the exposure. Circulation 2005;112:19-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bokhari SA, Khan AA. The relationship of periodontal disease to cardiovascular diseases-review of literature. J Pak Med Assoc 2006;56:177-81. [PubMed]

- Holmlund A, Holm G, Lind L. Number of teeth as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality in a cohort of 7,674 subjects followed for 12 years. J Periodontol 2010;81:870-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Little JW. Periodontal disease and heart disease: are they related? Gen Dent 2008;56:733-7; quiz 738-9, 768.

- Niedzielska I, Janic T, Cierpka S, et al. The effect of chronic periodontitis on the development of atherosclerosis: review of the literature. Med Sci Monit 2008;14:103-6. [PubMed]

- Teng YT, Taylor GW, Scannapieco F, et al. Periodontal health and systemic disorders. J Can Dent Assoc 2002;68:188-92. [PubMed]

- Rivas-Tumanyan S, Campos M, Zevallos JC, et al. Periodontal disease, hypertension, and blood pressure among older adults in Puerto Rico. J Periodontol 2013;84:203-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsakos G, Sabbah W, Hingorani AD, et al. Is periodontal inflammation associated with raised blood pressure? Evidence from a National US survey. J Hypertens 2010;28:2386-93. [PubMed]

- Tsioufis C, Kasiakogias A, Thomopoulos C, et al. Periodontitis and blood pressure: The concept of dental hypertension. Atherosclerosis 2011;219:1-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Relationship of cigarette smoking to attachment level profiles. J Clin Periodontol 2001;28:283-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Renvert S, Lindahl C, Roos-Jansaker AM, et al. Short-term effects of an anti-inflammatory treatment on clinical parameters and serum levels of C- reactive protein and pro-inflammatory cytokines in subjects with periodontitis. J Periodontol 2009;80:892-900. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Asikainen SE. Periodontal bacteria and cardiovascular problems. Future Microbiol 2009;4:495-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kornman KS, Duff GW. Candidate genes as potential links between periodontal and cardiovascular diseases. Ann Periodontol 2001;6:48-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Machtei EE, Christersson LA, Grossi SG, et al. Clinical criteria for the definition of “established periodontitis”. J Periodontol 1992;63:206-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Löe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. Acta Odontol Scand 1963;21:533-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Russell AL. Epidemiology of periodontal disease. Int Dent J 1967;17:282-96. [PubMed]

- Wiebe CB, Putnins EE. The periodontal disease classification system of the American Academy of Periodontology-an update. J Can Dent Assoc 2000;66:594-7. [PubMed]

- Molloy J, Wolff LF, Lopez-Guzman A, et al. The association of periodontal disease parameters with systemic medical conditions and tobacco use. J Clin Periodontol 2004;31:625-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kannel WB. Elevated systolic blood pressure as a cardiovascular risk factor. Am J Cardiol 2000;85:251-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buhlin K, Gustafsson A, Hakansson J, et al. Oral health and cardiovascular disease in Sweden. Results of a national questionnaire survey. J Clin Periodontol 2002;29:254-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chrysanthakopoulos NA, Chrysanthakopoulos PA. Examination of the relation between periodontal disease indices and self-reported coronary heart disease. Balk Mil Med Rev 2016;19:1-9. [Crossref]

- Hung HC, Colditz G, Joshipura KJ. The association between tooth loss and the self-reported intake of selected CVD-related nutrients and foods among US women. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2005;33:167-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chrysanthakopoulos NA, Oikonomou AA, Chrysanthakopoulos PA, et al. Association between periodontal disease parameters and coronary heart disease in Greek adults: A cross-sectional study. Int J Exp Dent Science 2015;4:4-10. [Crossref]

- Morrison HI, Ellison LF, Taylor GW. Periodontal disease and risk of fatal coronary heart and cerebrovascular diseases. J Cardiovasc Risk 1999;6:7-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pejcic A, Kesic L, Brkic Z, et al. Effect of periodontal treatment on lipoproteins levels in plasma in patients with periodontitis. South Med J 2011;104:547-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Starkhammar Johansson C, Richter A, Lundström A, et al. Periodontal conditions in patients with coronary heart disease: a case-control study. J Clin Periodontol 2008;35:199-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Page RC, Eke PI. Case definitions for use in population based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol 2007;78:1387-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chrysanthakopoulos NA, Chrysanthakopoulos PA. Clinically Classified Periodontitis and Its Association in Patients With Pre-existing Coronary Heart Disease. J Oral Dis 2013;1-9:243736.

- Latronico M, Segantini A, Cavallini F, et al. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease: an epidemiological and microbiological study. New Microbiol 2007;30:221-8. [PubMed]

- Chrysanthakopoulos NA, Chrysanthakopoulos PA. Associations among patients with periodontal and systemic Disorders. Oral Health Prev Dent 2013;11:251-60. [PubMed]

- Chrysanthakopoulos NA, Chrysanthakopoulos PA. Examination of the Relation Between Periodontal Disease Indices in Patients with Systemic Diseases. Acta Stomatol Croat 2013;47:217-32. [Crossref]

- Chrysanthakopoulos NA, Chrysanthakopoulos PA. Association Between Clinically Defined Periodontitis And Self-Reported History of Systemic Medical Conditions. J Investig Clin Dent 2016;7:27-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tuominen R, Reunanen A, Paunio M, et al. Oral health indicators poorly predict coronary heart disease deaths. J Dent Res 2003;82:713-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hujoel PP, Drangsholt M, Spiekerman C, et al. Examining the link between coronary heart disease and the elimination of chronic dental infections. J Am Dent Assoc 2001;132:883-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Chrysanthakopoulos NA, Oikonomou AA. Periodontal disease as a possible risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases in a Greek adult population. Ann Res Hosp 2017;1:15.